Motivation and Chunking |

Introduction

The language that people use can give us a clue to what triggers their motivation. Motivation is the ‘call to action’ that causes us to act or respond in a certain way.

Internal forces such as basic needs, desires and drivers motivate our behaviours. Incentives, rewards and reinforcement are external means of motivating our behaviours. These are commonly known as intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Sigmund Freud came up with a motivational theory called the ‘pleasure principle’. According to Freud we are driven to either ‘seek pleasure or avoid pain’. The Greek philosopher Aristotle’s theory mirrors that of Freud, in that we are motivated by an appetite for the, potential, consequences of our actions.

In addition to pain and pleasure, needs and drivers are also associated with motivation. Basic human needs such as food, air, water and sleep are needs. If food is lacking and we feel deprived, our drive to maintain homeostasis kicks in, a natural balance, and we are motivated to eat. This happened even if we just think we are feeling deprived. Deprivation means ‘pain’ which is something that we want to move away from. Satiety is ‘pleasure’, something that we want to move towards.

Internal forces such as basic needs, desires and drivers motivate our behaviours. Incentives, rewards and reinforcement are external means of motivating our behaviours. These are commonly known as intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Sigmund Freud came up with a motivational theory called the ‘pleasure principle’. According to Freud we are driven to either ‘seek pleasure or avoid pain’. The Greek philosopher Aristotle’s theory mirrors that of Freud, in that we are motivated by an appetite for the, potential, consequences of our actions.

In addition to pain and pleasure, needs and drivers are also associated with motivation. Basic human needs such as food, air, water and sleep are needs. If food is lacking and we feel deprived, our drive to maintain homeostasis kicks in, a natural balance, and we are motivated to eat. This happened even if we just think we are feeling deprived. Deprivation means ‘pain’ which is something that we want to move away from. Satiety is ‘pleasure’, something that we want to move towards.

Carrot & Stick

What will trigger a person into action? Do they want to move towards an outcome or reward, (a carrot) or do they want to move away from a problem to be solved or prevented (a stick)?

Everyone will be motivated differently in varied contexts. The way someone is motivated in health may be very different to the way they are motivated in business. Therefore, the following motivational theories are context specific.

Everyone will be motivated differently in varied contexts. The way someone is motivated in health may be very different to the way they are motivated in business. Therefore, the following motivational theories are context specific.

Towards Motivation

In any given context, people who are motivated in a towards pattern are focussed on their goal and what they have to achieve. They are motivated to have, get, achieve, attain, be and so on (obtain ‘pleasure’ and feel good).

They are excited and energised by their goals. As a result, they may have difficulty in identifying problems and trouble-shooting. At an extreme, they can be perceived as naïve as they do not always take potential obstacles into account. Examples are being motivated towards:

They are excited and energised by their goals. As a result, they may have difficulty in identifying problems and trouble-shooting. At an extreme, they can be perceived as naïve as they do not always take potential obstacles into account. Examples are being motivated towards:

- An award

- A medal

- Recognition from others

- Wealth

- Good health

- Respect

- Fame

- Feeling slim or muscular

- Feeling attractive

- Bring in a relationship

Away From Motivation

In any given context, people who are motivated in an away from pattern notice what should be avoided and gotten rid of, otherwise not happen. Their motivation is triggered when there is a problem to be solved or an uncomfortable situation to move away from (pain). They are energised by threats. Here are some examples of things people are motivated to move away from:

Once we understand the pattern of motivation, either towards or away from, we can use the appropriate language and incentives to support motivation for that individual.

- Poor health

- Financial difficulty

- Clothes that don’t fit

- Getting out of breath walking up stairs

- Criticism from others

- Feeling unattractive

- Being out of work

- Being single

Once we understand the pattern of motivation, either towards or away from, we can use the appropriate language and incentives to support motivation for that individual.

Influencing Language

Towards – attain, have, get, be, include, obtain etc.

Away from – avoid, prevent, steer clear of, eliminate, solve etc.

In order to determine if someone is motivated towards or away from we need to ask a simple question three times. The question is:

WHY IS THAT IMPORTANT? (ASK 3 TIMES)

For example:

Client – I WANT BE SLIMMER

Coach – Why is being slimmer important to you?

Client – BECAUSE I’LL LOOK AND FEEL BETTER

Coach – Why is looking better important to you?

Client – BECAUSE I WANT TO MEET MR RIGHT!

Coach – Why is meeting Mr Right important to you?

Client – Because I don’t want to end up lonely

The last statement made by the client, in this case, is an away from comment. It’s what she doesn’t want to happen that is motivating her to be slimmer. As an NLP coach, we can support this motivation by reminding the client what she is avoiding or preventing by working on being slimmer.

Many people and organisations think that offering rewards, incentives and bonuses are the only way to motivate others and this does work for some people. However, a strong desire to avoid or get rid of something can be even more powerful for others. In fact, Anthony Robbins, international Life Coach and Motivation guru, says that people, generally, are far more motivated by pain than they ever will be by pleasure.

When we ask, “Why is that important?” we are also uncovering a person’s values. We have values that we want to move towards and values that we want to move AWAY FROM. The table below shows examples these values.

Away from – avoid, prevent, steer clear of, eliminate, solve etc.

In order to determine if someone is motivated towards or away from we need to ask a simple question three times. The question is:

WHY IS THAT IMPORTANT? (ASK 3 TIMES)

For example:

Client – I WANT BE SLIMMER

Coach – Why is being slimmer important to you?

Client – BECAUSE I’LL LOOK AND FEEL BETTER

Coach – Why is looking better important to you?

Client – BECAUSE I WANT TO MEET MR RIGHT!

Coach – Why is meeting Mr Right important to you?

Client – Because I don’t want to end up lonely

The last statement made by the client, in this case, is an away from comment. It’s what she doesn’t want to happen that is motivating her to be slimmer. As an NLP coach, we can support this motivation by reminding the client what she is avoiding or preventing by working on being slimmer.

Many people and organisations think that offering rewards, incentives and bonuses are the only way to motivate others and this does work for some people. However, a strong desire to avoid or get rid of something can be even more powerful for others. In fact, Anthony Robbins, international Life Coach and Motivation guru, says that people, generally, are far more motivated by pain than they ever will be by pleasure.

When we ask, “Why is that important?” we are also uncovering a person’s values. We have values that we want to move towards and values that we want to move AWAY FROM. The table below shows examples these values.

Values to move TOWARDS |

Values to move AWAY FROM |

Love, family, success, challenge,adventure, security, status, career, health, freedom, peace, connection, contribution, pride, committed |

Love, fear, guilt, shame, prejudice, failure, insecurity, loneliness, disappointment, conflict, boredom, committed, challenge, adventure |

Some people value challenge highly, whilst others will do anything to avoid it. Neither is right or wrong, they are just different. Knowing what values our clients want to move towards and away from is key to unlocking their motivation and their potential.

Stages of Change

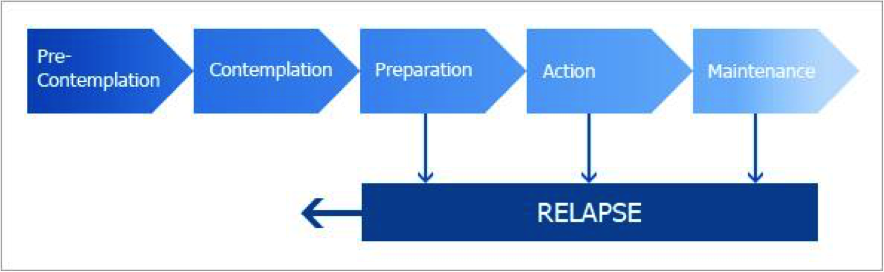

Prochuska and Diclimente (1977) gave us the Transtheoretical Model, more commonly known as the Stages of Change Model.

The model arose from studying a range of people who were considered to be self-changers. For example they had lost weight, stopped smoking, given up drinking or escaped depression on their own and maintained the change over a period of time. It is from the ‘patterns’ that emerged within each individual mental map that the model emerged.

The diagram below illustrates the five stages of change set out in this model.

The model arose from studying a range of people who were considered to be self-changers. For example they had lost weight, stopped smoking, given up drinking or escaped depression on their own and maintained the change over a period of time. It is from the ‘patterns’ that emerged within each individual mental map that the model emerged.

The diagram below illustrates the five stages of change set out in this model.

- Pre-contemplation: not intending to make any changes.

- Contemplation: considering a change.

- Preparation: making plans for change (e.g. joining a health club)

- Action: actively engaging in a new behaviour and gaining results

- Maintenance: sustaining the change over time.

The self-changers had all followed the model step by step at an unconscious level. Little known to them, at the time, they had all adhered to the same pattern of thinking and therefore behaviour.

For most of us, however, these stages do not always occur in a linear fashion (simply moving from 1 to 5). The theory describes behaviour change as dynamic. For example, an individual may move to the preparation stage and then back to the contemplation stage several times before progressing to the action stage. New Year’s resolutions are a typical example of someone moving from contemplation straight into action phase. Having skipped the preparation phase completely, it is easy for relapse to occur back to an earlier stage. Conversely, some people spend their lives in the preparation stage and never actually progress to taking action!

Preparation is a key phase for permanent behaviour change; unfortunately it often gets overlooked as people leap into action. As an NLP coach, it is important that we help our clients to be well prepared for the change that awaits them. Preparing their environment at home and at work to support them; learning new skills where necessary; understanding the importance of making change and self-belief; understanding who they will be if they were to change and ultimately how they could make a difference. This prepares someone over the whole scope of neurological levels for change.

Remember that change does not happen in one step. For new behaviours and actions to be lasting, change has to happen in stages. Different people will progress through the stages at different rates. A person who is contemplating giving up drinking isn’t ready to join an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, and to suggest otherwise may be counter-productive. They will need to grapple with issues and prepare for that action to take place. Some of the NLP interventions and exercises previously covered will help to support preparation over all levels and, therefore, alignment and agreement for action to take place.

Chunking

As previously discussed, we tend to make generalisations. This is very useful when we are learning something new. For instance, when we learn how to drive a car, we are taught to do it step by step. We will initially concentrate on our feet, hands, mirrors etc. in turn, and be fully aware of them at all times. As we become more competent drivers we generalise these steps into ‘just driving’. We will have become unconsciously competent and think of driving as a set of actions that have been rolled into one.

However, generalisations can limit us also. For someone who has a lot of weight to lose the task in hand can seem overwhelming. Being able to focus on smaller steps can help to keep them from being overwhelmed so goals and action plans need to be ‘chunked down’ into bite size pieces in order for action to take place. Conversely, client’s might well be overwhelmed by detail and too narrowly focussed, and thus limited by neglecting possibilities beyond their narrow scope. Being able to consider a bigger ‘chunk’ can expand their perspective. People have preferences about the chunk size level at which they think, work and communicate. In order to coach effectively, we must be able to recognise and adjust our own thinking and communication chunk size.

BIG CHUNK THINKERS

Big chunk thinkers are planners and visionaries. They see the big picture and taking a bird’s eye view is their skill. These people make great strategists, and leaders. They will work best with a general plan of information. If they are offered too much detail they will get bored and lose interest.

To help these people we need to move them from their generalisation to the specific, to give examples of what we are talking about, to sequence detail. This is referred to as Chunking Down .

If we have a client who is generalising too much to take action, and we want to chunk down their thinking, we need to ask questions like:

SMALL CHUNK THINKERS

Small chunk thinkers tend to be the technicians. They thrive on detail and specifics. They need to know detail in terms of where, what and who. They are excellent at turning an idea into a procedure. These people will crave a detailed plan of action. For these people the big picture can feel meaningless and even irritating.

If, when we are learning, the steps to a task remain as pieces then we will not develop an understanding of how all of the pieces fit together. The ability to bring all the pieces together to form a more general picture is called Chunking Up.

There can come a point when a client can feel overwhelmed by all the information they have gathered. This is especially true of individuals experiencing stress. We need to help them to chunk up to a higher level of thinking. To help others to develop their skill at chunking up we need to ask:

CHUNKING ACROSS

This happens when we seek to find similarities with other situations and in other contexts. This can add credibility to the situation and helps to fill gaps in understanding. Finding equivalent information or examples in another context is called chunking across.

To help to develop skills at chunking across, we need to ask:

As with all other NLP distinctions, it is important to have flexibility in being able to move our attention from the big picture to detail and offer examples to generate a deeper understanding in any situation.

METAPHORS

Metaphors are a useful tool to help us to chunk across. The word metaphor is derived from the Greek and literally means to ‘carry across’. Broadly speaking, NLP defines metaphor in terms of stories,

analogies or figures of speech that imply a comparison or parallel between two, sometimes unrelated, situations. They are a useful tool, in helping to explain complex issues.

Explaining how the human metabolism works can be complex if we only use literal language. Conversely, using the metaphor of a car, we can draw comparisons:

Our everyday language will be littered with metaphors. Consider these examples:

A metaphor paints a thousand words. It appeals to all the representational systems (VAKOG) and allows the unconscious mind to explore and expand understanding. Metaphors are a useful communication tools and help to aid memory.

Creating a metaphor is as easy as asking ourselves “It’s a bit like what?”

For example:

Your in trouble if you do that = It’s a bit like driving towards a wall of fire

Or:

I need a good team around me =I need strikers, defenders and those that can take up the mid field

Noticing and pacing the metaphors used by our clients is a useful way to deepen rapport. We can even expand on the metaphors offered to guide thinking towards a solution. For example, if a client’s says that they feel like they are hitting their head against a brick wall, we could ask:

Expanding metaphors is a way of working with the unconscious mind and directing it towards finding a solution. This is often the approach used in hypnotherapy and also works equally well in a normal every day level of awareness.

However, generalisations can limit us also. For someone who has a lot of weight to lose the task in hand can seem overwhelming. Being able to focus on smaller steps can help to keep them from being overwhelmed so goals and action plans need to be ‘chunked down’ into bite size pieces in order for action to take place. Conversely, client’s might well be overwhelmed by detail and too narrowly focussed, and thus limited by neglecting possibilities beyond their narrow scope. Being able to consider a bigger ‘chunk’ can expand their perspective. People have preferences about the chunk size level at which they think, work and communicate. In order to coach effectively, we must be able to recognise and adjust our own thinking and communication chunk size.

BIG CHUNK THINKERS

Big chunk thinkers are planners and visionaries. They see the big picture and taking a bird’s eye view is their skill. These people make great strategists, and leaders. They will work best with a general plan of information. If they are offered too much detail they will get bored and lose interest.

To help these people we need to move them from their generalisation to the specific, to give examples of what we are talking about, to sequence detail. This is referred to as Chunking Down .

If we have a client who is generalising too much to take action, and we want to chunk down their thinking, we need to ask questions like:

- What is an example of this?

- What specifically would be an example?

- What would this allow you to do?

- When do you do this? When could this be done?

- What is a baby step you can take towards that?

SMALL CHUNK THINKERS

Small chunk thinkers tend to be the technicians. They thrive on detail and specifics. They need to know detail in terms of where, what and who. They are excellent at turning an idea into a procedure. These people will crave a detailed plan of action. For these people the big picture can feel meaningless and even irritating.

If, when we are learning, the steps to a task remain as pieces then we will not develop an understanding of how all of the pieces fit together. The ability to bring all the pieces together to form a more general picture is called Chunking Up.

There can come a point when a client can feel overwhelmed by all the information they have gathered. This is especially true of individuals experiencing stress. We need to help them to chunk up to a higher level of thinking. To help others to develop their skill at chunking up we need to ask:

- What would this be an example of?

- What is the purpose of this?

- What would this give you?

- What’s important about this?

- And if you were to do that what might happen?

CHUNKING ACROSS

This happens when we seek to find similarities with other situations and in other contexts. This can add credibility to the situation and helps to fill gaps in understanding. Finding equivalent information or examples in another context is called chunking across.

To help to develop skills at chunking across, we need to ask:

- What is another example of this?

- Where else would you find this?

- What other experiences have you had of this, or something similar?

- Where else could you use this?

As with all other NLP distinctions, it is important to have flexibility in being able to move our attention from the big picture to detail and offer examples to generate a deeper understanding in any situation.

METAPHORS

Metaphors are a useful tool to help us to chunk across. The word metaphor is derived from the Greek and literally means to ‘carry across’. Broadly speaking, NLP defines metaphor in terms of stories,

analogies or figures of speech that imply a comparison or parallel between two, sometimes unrelated, situations. They are a useful tool, in helping to explain complex issues.

Explaining how the human metabolism works can be complex if we only use literal language. Conversely, using the metaphor of a car, we can draw comparisons:

- A Rolls Royce needs more fuel than a mini

- We slow down to conserve fuel when the empty light appears on the dash board

- Performance cars need quality fuel

- The quality of fuel will determine the emissions from the exhaust!

Our everyday language will be littered with metaphors. Consider these examples:

- It’s like hitting my head against a brick wall

- She’s a pain in the neck

- He’s a breath of fresh air

- It’s a jungle out there

- It’s like getting blood from a stone

- They go together like a lock and key

A metaphor paints a thousand words. It appeals to all the representational systems (VAKOG) and allows the unconscious mind to explore and expand understanding. Metaphors are a useful communication tools and help to aid memory.

Creating a metaphor is as easy as asking ourselves “It’s a bit like what?”

For example:

Your in trouble if you do that = It’s a bit like driving towards a wall of fire

Or:

I need a good team around me =I need strikers, defenders and those that can take up the mid field

Noticing and pacing the metaphors used by our clients is a useful way to deepen rapport. We can even expand on the metaphors offered to guide thinking towards a solution. For example, if a client’s says that they feel like they are hitting their head against a brick wall, we could ask:

- What needs to happen to knock that wall down?

- How can you climb over the wall?

- Where are the edges of the wall and how can you walk round it?

- What do you need to be able to do to reach the other side of that wall?

Expanding metaphors is a way of working with the unconscious mind and directing it towards finding a solution. This is often the approach used in hypnotherapy and also works equally well in a normal every day level of awareness.